Copper-based compounds have served people for centuries. Whether seen in ancient pigments, early medicine, or as a line of defense against plant diseases, copper stands out for its antimicrobial properties and chemical versatility. The story stretches from old-world copper salts to modern organometallics. Copper isooctanoate, often called copper 2-ethylhexanoate, traces roots to the mid-20th century when chemists began pairing carboxylic acids with metal salts for tailored reactivity. Companies sought metal carboxylates that dissolved in organic solvents without clumping or separating. This allowed for innovation in paint dryers, wood preservatives, and plastic stabilizers. During the rapid development of plastics and coatings in the post-war era, copper isooctanoate began its climb as a solution for industries in need of an oil-soluble, low-toxicity copper source. Patents flooded in through the 1960s and 1970s, each improving on production, solubility, or safety. By the end of the twentieth century, copper isooctanoate became a quiet stalwart for chemists aiming to harness copper’s reactivity in organic systems.

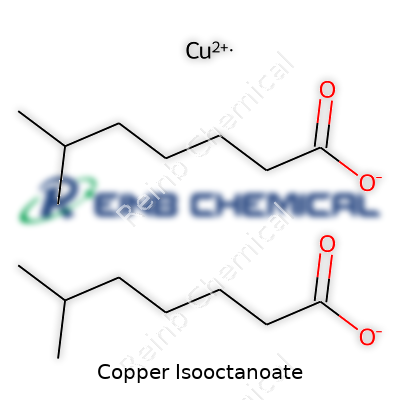

Copper isooctanoate lands chemically as a copper salt of 2-ethylhexanoic acid. Familiarly known as copper octoate or copper 2-ethylhexanoate, this compound takes the form of a blue-green viscous liquid or oily solid, depending on purity and the surrounding temperature. Chemists and users value it for its ability to dissolve in organic solvents, lending copper’s unique properties to oil- and solvent-based paints, catalysts, and agricultural treatments. Because the copper center is nestled within two bulky, oily chains, the molecule avoids clumping and remains stable under typical atmospheric conditions, which simplifies handling and extends shelf life.

Copper isooctanoate shows up as a blue to blue-green liquid with a faint, oily odor. Those handling it know it stains skin and surfaces quickly and leaves a stubborn residue. Its solubility in basic oil solvents sets it apart from water-loving copper compounds like copper sulfate, letting formulators work with copper in systems that water would disrupt. The usual technical grade gives a copper content of about 8–10%, balancing copper’s potency with the processability brought by the isooctanoate group. The compound melts around room temperature, with viscosity making automated pumping tricky without heating. Its molecular weight hovers near 405 g/mol, and the density rests around 1.1–1.2 g/cm³. The fatty acid ligands prevent rapid air and light degradation, though over time and with improper storage, oxidation turns the liquid darker and thickens it.

Producers commonly state copper concentration, acid value, and free acids on labels because end-users rely on these three numbers to fit their formulas. Copper typically hovers between 8–10%. The acid value, measuring unreacted acid (mg KOH per gram), should stay low; high acid content leads to corrosion or side reactions. Water and volatiles get checked since trace water causes unwanted foaming or hydrolysis in paints and plastics. Labels require hazard warnings—irritant symbols, safety advice for skin and eye contact, and a note about environmental risk if spilled near water. In Europe and parts of Asia, registration numbers appear for tracking under chemical control rules.

The process starts with 2-ethylhexanoic acid and a copper salt, usually copper carbonate or copper hydroxide. Acid and copper source go together in a glass or stainless steel mixer. Heat the mixture gently; a light green or blue color takes over as the copper dissolves into the organic phase. Bubbles of CO₂ escape. The product is washed to remove unreacted mineral particles, then dried under vacuum or by gentle heating. Purity matters—unreacted acid or excess water ruins performance in most industrial formulations. Producers control temperature and stirring to avoid entraining water or forming tar-like residues. Yield usually tops 95%. The end result is a dense blue liquid, ready to bottle or ship.

Copper isooctanoate opens doors for further chemistry. It slips into organic solvent systems without fuss, and because the copper lies in an oil-soluble shell, reaction with organic substrates, polymers, or other metal carboxylates proceeds without precipitation or phase separation. It acts as a mild oxidant, triggering polymer crosslinking or acting as a colorant when cured at low temperatures. The isooctanoate portion can be swapped for other carboxylates if special reactivity or volatility is needed, letting manufacturers custom-tailor their ingredients. I’ve seen decorators take copper octoate and blend it into alkyd or urethane varnishes, triggering faster cure, deeper color, and enhanced mildew resistance compared to standard metal dryers. If cosolvents and catalysts are present, copper isooctanoate helps form uniform copper oxide particles for electronics or catalysis.

Copper isooctanoate wears several labels in trade and science circles. Some refer to it as copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate, copper octanoate, or copper octoate. The abbreviation Cu(Oct)₂ sometimes marks research chemistry catalogs. English and global labeling remain in flux, so product sheets may list “Copper 2-ethylhexanoate” or “Octanoic acid, copper salt” on top of commercial product names from major suppliers. European and Asian chemical inventories tend to prefer the IUPAC-style names; old-school formulators might know it only by “copper naphthenate” or “copper carboxylate” rather than its precise structure, reflecting a tradition of messy naming in metal-organics.

Handling copper isooctanoate involves a mix of respect and routine. Those in paint and plastics plants know the oily blue stains and the mild, metallic odor. Splash it on skin and blue-green marks linger for days. Safety data sheets make it plain: direct contact can irritate skin or eyes and sometimes trigger an allergic response. Chronic exposure demands gloves and goggles—copper’s trace toxicity means not taking any chances. Spilled liquid behaves like a low-viscosity oil, spreading rapidly and contaminating surfaces. Environmental rules require bunded storage and careful mixing to avoid leaks into local water systems. Waste handling focuses on copper recovery, and spent drums clean out in specialist recyclers certified to handle copper residues. In daily use, workers stick to mechanical, well-ventilated filling to avoid inhalation or splashing.

Most copper isooctanoate gets snapped up by paint and coating manufacturers. They value its ability to crosslink with resins during curing, boosting hardness and mildew resistance in marine and exterior paints. The same copper ions fight wood rot, earning the compound a place in high-end wood preservatives and varnishes. Plastic manufacturers feed copper isooctanoate to vinyl and polyurethane systems, where it stabilizes heat-induced oxidation and limits discoloration from mold or UV attack. In the world of agriculture, chemists experiment with formulations to fight downy mildew, powdery mildew, and grapevine diseases—though copper’s environmental load pushes farmers to look for greener alternatives. Electronics developers use the compound as a precursor, decomposing it in controlled conditions to form copper oxides and thin films for printed circuit boards or sensors.

The R&D scene for copper isooctanoate bustles with activity. Formulation chemists keep tweaking the acid content and purity to deliver better stability—especially under hot, humid warehouse conditions. Studies run on optimal copper loadings for wood preservation, with researchers debating the balance between effectiveness against rot and minimal copper leaching. Green chemistry teams test bio-based modifications of the isooctanoate group, aiming to keep copper in the mix but swap petro-derived acids for plant-derived alternatives. On the electronics side, material scientists explore new reduction pathways to turn copper isooctanoate into high-purity metal films or nanoparticles without side products. Academic labs publish new reactions using copper isooctanoate as a catalyst in organic chemistry, looking for routes that deliver selective oxidation or polymerization. Industry players invest in surfactant blends and stabilizers that keep copper isooctanoate flowing well—no clogs, no separation, just consistent feed to the paint mixer or plastics extruder.

Copper occupies a strange space between nutrient and toxin. Trace amounts matter for plant and animal health, but overexposure can tip the scales fast. Toxicity testing for copper isooctanoate looks not just at acute exposure—the risks from getting the chemical on skin or in eyes—but also at the long-term effects of copper buildup in aquatic and soil environments. The oily isooctanoate group helps keep copper from rushing straight into water, though accidental spills or disposal can still deliver a shock dose to streams and creatures. Chronic animal studies link high copper exposure with liver and kidney effects; copper isooctanoate doesn’t escape scrutiny, even with its lower water solubility. Regulators demand breakdown and leaching studies, measuring how much copper migrates to soil or water over years. The verdict: use with care, never dump, and keep workers protected. One key topic in recent years is how nanoparticles formed from copper isooctanoate interact with living cells and how fine copper particles move through the food web.

Looking decades ahead, I don’t see copper isooctanoate fading any time soon, but its forms and uses will keep changing. Environmental pressure keeps pushing for “greener” versions—biodegradable ligands, copper-recycling systems, even nanoencapsulation to limit runoff in wood treatments or agriculture. Research teams aim for lower toxicity and less copper loss without sacrificing the mold and algae resistance that makes the chemical valuable. The electronics industry eyes it as a cheaper, “solution-processable” feedstock for copper wiring in flexible circuits and solar cells, fueling demand for ultra-pure versions. Paints and plastics manufacturers want purer, more flowable forms, so process engineers improve drying, blending, and packaging methods. The challenge stays the same: pulling all the benefits of copper without tipping over into environmental harm or regulatory bans. Collaboration between industry, academia, and regulators will keep this compound evolving while meeting health and sustainability targets. The role of copper isooctanoate shifts, but its importance remains, especially if researchers crack the code for truly green, high-performing organometallics.

Ask anyone who grows tomatoes, grapes, or apples—plant diseases can ruin an entire season’s hard work. Copper isooctanoate delivers copper in a form that plants absorb well, acting as a shield against fungi and bacteria.

Unlike older copper sprays that coat everything a bright blue, this compound goes on invisible and sticks around longer, even in rainy conditions. Farmers rely on it because fungal problems like downy mildew do not pause because of weather, and skipping a treatment can mean disaster. In my experience helping manage a family orchard, those brown spots that show up overnight do not care about cost or eco-friendliness. Growers look for answers that work right away, and copper isooctanoate often steps in where milder products fail. The compound’s structure helps copper ions cling to leaves, making every sprayed dollar count.

Organic growers face tight rules—they cannot just spritz any old chemical onto lettuce or vine crops. Copper isooctanoate can fit under these rules in limited doses, which makes it precious for those who want a label that says “no synthetic pesticides.” Every bottle of organic wine or heirloom tomato owes something to finding compounds that work and pass government checks.

After all, most folks do not want extra copper in their food, and government bodies know this. Strict rules say how much total copper can touch crops each season. Smart use means disease control without crossing the line, making copper isooctanoate a key player for both safety and crop value.

Wood rots quickly in damp places—think railroad ties, barns, or playground equipment. By soaking wood with copper isooctanoate, people keep mold, termites, and other rot away. It seeps in deeper than many copper treatments, and it does not wash out fast in storms.

I have seen fence posts still standing strong a decade after others around them crumbled, all because they were treated early with a copper-based solution. Projects meant to last, especially outdoors, benefit from a preservative that will not flake away or poison the soil nearby.

Copper does not just disappear. Runoff from large-scale farming or careless wood treatment can add up in rivers and lakes. High copper levels make it hard for aquatic life to thrive. Weighing disease control against water health takes serious thought.

Smarter sprayers, soil testing, and following strict timing can cut down on risk. Some farmers I know have moved to lower rates or skip copper if the weather forecast gives them room. Others look for alternate treatments but keep copper isooctanoate as a backup when safer options fail. Sharing honest research and listening to scientists helps everyone balance crop health and clean streams.

Copper isooctanoate does not promise a cure-all for food security or outdoor preservation. It fills a clear need in keeping plants, wood, and water safe when options run thin. Safer packaging, education, and government standards will keep its use responsible. On every field or construction site, the choice always comes down to protecting investment while not trading away the future. Copper isooctanoate, for all its chemistry, ends up being about practical choices for today and tomorrow.

The search for reliable crop protection keeps drawing farmers and scientists toward different copper-based products. Copper isooctanoate shows up as one of those new alternatives popping up on the market. It’s being pitched as a fungicide, sometimes even as a micronutrient. The real question for anyone growing food or working with land is: can we trust it?

I’ve spent years on farmland, and the decisions around crop treatment always run deeper than product labels or sales pitches. The idea of copper isooctanoate brings some natural skepticism—especially with so many chemicals winding up in unexpected places. Farmers don’t just want healthy fields today but also land that keeps producing for decades. Copper itself isn’t new in agriculture; copper sulfate and other compounds have been standard tools for blight and fungus. Still, every copper compound acts a bit differently.

Agricultural agencies have tested some copper isooctanoate products and list them as low-risk under certain guidelines, based on studies about toxicity to humans and animals. Crops treated with this compound haven’t turned up dangerous residues in the edible portions when used by the book. I’ve spoken with growers who monitor their own field runoff. They worry less about direct health risks and more about what shows up in stream water and soil after repeated use. Copper does not degrade like organic compounds; it builds up, and if copper levels run high, certain plants, earthworms, and aquatic life can suffer.

Long-term use is where doubts gather. Decades of copper buildup from older fungicides already create problems in vineyard soils across the world. Healthy soil means more than just feeding the plants. Microbes and bugs feed everything higher up the food chain. I’ve seen soil tests from fruit orchards with years of copper treatments that reveal stunted insect life—not just a pest reduction, but a full-scale drop in living creatures. Copper is copper, no matter the form, so the main risk always circles back to accumulation, not the immediate dose.

The US Environmental Protection Agency, along with similar groups in Europe and Asia, puts strict limits on how and when copper isooctanoate gets sprayed. Most labels call for limited application rates and days-to-harvest intervals. Growers get required to document product use, record any incidents, and sometimes test groundwater in sensitive areas. So far, no large outbreaks of copper poisoning have come from these products on food crops, but regulators remain cautious.

Crop specialists often remind their clients that copper should be the last line, not the first. Crop rotation, attentive scouting, and basic field hygiene cut down on most fungal outbreaks before any chemical sees the sprayer. Some organic farms pick copper isooctanoate because older fungicides have heavier footprints or have run into bans. Even then, the best growers rotate away from copper products, blend in compost, and test their soils every few years for heavy metals.

Unless innovation delivers a magic bullet, the best route remains careful tracking of every spray across seasons. Whether using copper isooctanoate or older blue powders, farmers find safety by knowing what enters their land, how much, and what’s left behind. A safe field isn’t just a productive one—it’s a place that supports life above and below the surface. That’s the true test for any agricultural chemical, new or old.

People working in agriculture and horticulture recognize copper compounds for their important role in fighting fungal diseases and supporting plant growth. Copper Isooctanoate stands out because it’s an oil-soluble copper salt, which means it mixes well with oil-based sprays and sticks better to plant surfaces.

A typical dosage mentioned by manufacturers and crop advisors ranges between 100 and 300 milliliters per 100 liters of water. This range covers most foliar applications for vegetables, ornamentals, and fruit crops. I’ve seen tomato and pepper growers keep close to the lower end, around 120–150 milliliters in 100 liters, primarily out of caution. Overuse can burn leaves and walnuts in young tissue. Grapevine growers dealing with persistent fungal problems—even after rainy spells—sometimes use higher rates but always pay close attention to crop sensitivity and mixing partners.

Field experience counts for a lot. On busy summer mornings, I’ve watched agronomists test dilution rates in small spots before moving to full-field application. Small-scale trials catch unexpected reactions and prevent serious mishaps. It matters especially in humid climates, where copper tends to accumulate if rains come too frequently. Copper toxicity sneaks up fast with repeated use.

Using too little won’t suppress fungal outbreaks and often lets diseases rebound. Citrus groves hit by greasy spot or scab can turn around only when copper is present at the right concentration and re-applied in line with rainfall and infection pressure. Swinging too far the other way causes tip burn on leaves or hinders new root growth, both of which stunt yields. I remember citrus farmers in southern regions facing tough choices—if they raised copper rates to combat blight, their young shoots curled and dropped. A strong harvest needs a balanced strategy.

Soil type, crop age, disease load, and recent rainfall guide most real-world adjustments. Sandy soils with less organic matter can show toxicity sooner. Old, established trees, especially those on less copper-sensitive rootstocks, tolerate marginally higher rates. I’ve seen community-run farms rely on extension bulletins from universities or consortia, but few skip reading the product label. Regulations in some countries set strict maximum residue limits (MRLs) so crops stay safe to eat; staying within these ensures legal compliance as well as food safety.

Personal protection matters as well. Even when handling seemingly “mild” rates, gloves and masks stay on because copper solutions can irritate skin and lungs. Re-entry intervals—how long you wait before working in a treated area—show up in bold print for good reason. Accidents involving concentrated copper mix up or careless tank washout aren’t rare but always preventable with good habits.

Advice changes as plant science evolves. A few years ago, only a handful of copper formulations were available. Now, growers look for products that weather rainfall, minimize runoff, and hit challenging disease cycles at critical moments. Some labs are working to lower recommended rates further—keeping copper effective while less builds up in soil. Digital recordkeeping and local weather monitoring help dial in the best time and amount to spray, making overapplication less likely.

Relying on field observations, scientific data, and label guidance helps everyone from home gardeners to startup farmers. Using the lowest rate that gets the job done avoids wasted resources and protects both plants and people. Copper Isooctanoate plays an important role in modern plant care, but like every farm input, it calls for careful measurement, patience, and willingness to adapt as conditions change.

Copper Isooctanoate often shows up in plenty of industrial applications. Its unique properties make it a popular choice among chemists and manufacturers looking for an effective metal soap, catalyzing agent, or specialist ingredient in coatings and lubricants. This isn’t something you’d leave lying around, and there’s a reason lab supervisors pay close attention to its storage.

I remember sorting through an old stockroom at an aging facility. Some containers looked like they hadn’t moved in years—dusty, labels starting to peel, oily residue under the lids. Most issues come down to skipping steps or taking shortcuts. Leaving Copper Isooctanoate exposed speeds up deterioration and contamination, which leads to weaker performance and surprise downtime. Flammable vapors can pose bigger risks, especially where workers think a fume hood and a closed door will do the trick.

Proper storage starts with the container. Employees should always pick tight-sealing vessels made of compatible materials. Most manufacturers supply Copper Isooctanoate in metal or strong plastic drums for a reason. A careless seal lets air and moisture creep in, which triggers slow degradation and, in worse cases, chemical reactions that change the product’s nature.

Storing containers in a dry, well-ventilated spot makes a real difference. Damp corners invite mold and metal corrosion, so keeping stock high and clear of the floor helps. In my own workspace, shelves with strong metal brackets and raised edges work better than old wood or makeshift racks. Everyone knows to keep incompatible substances far away. Avoiding acids, oxidizers, and food products keeps employees safe and quality intact.

Copper Isooctanoate reacts poorly to big temperature swings. It should rest in an area with stable, moderate conditions, out of direct sunlight and away from machinery that gets hot. I’ve seen more than one crisis start from storage next to a heating vent. Room temperature serves most facilities well—usually between 15°C and 25°C—though cooler is sometimes better if turnover is slow.

In places where large drums are used, regular inspection stops damage before it spreads. Check for leaks, dents, or changes in color and smell. Leaks mean more than lost product; vapors and spills create long-term hazards. Good record-keeping tracks batch numbers and dates, making it simple to rotate stock and keep freshness in check. It always pays to use supplies closest to their expiration first.

Well-trained staff spot hazards faster. Regular training refreshes safety knowledge, including emergency procedures in case of spills or fire. It’s worth posting clear signage and up-to-date safety data sheets right where people store and handle this product. Eye and skin protection aren’t optional—splashes can sting, and no one wants to deal with stains on clothing or worse, lasting skin sensitivity.

Disposal counts too. Unneeded or expired material shouldn’t get tossed down a drain or in the regular trash. Working with a certified chemical waste handler ensures responsible management, keeping communities and the environment safe. Everyone on site benefits when handling, storing, and disposing of Copper Isooctanoate receives the same care as any other specialty chemical.

Copper Isooctanoate deserves respect through each step of its life. Smart storage builds safety into workplace routines, reduces long-term expenses, and guarantees the ingredient works the way it should. A well-organized system beats quick fixes or guesswork every time, making every shift safer and more predictable for everyone involved.

Mixing agrochemicals seems simple at first glance. Pour two things into a tank, spray, and call it a day. But most farmers and agronomists know that this can quickly go sideways. Years ago, I saw an orchard manager lose half a day unclogging nozzles after an incompatible mix turned his copper solution into sludge. Not only did he waste time and money, he risked under-protecting his trees. Compatibility matters because one bad tank mix doesn’t just hurt performance—it can take a toll on equipment, crop safety, and harvest quality.

Copper isooctanoate steps in as a liquid copper fungicide, promoted for its low-dust, easy-to-handle properties compared to older copper powders. It dissolves a lot better in spray tanks and sticks to plant surfaces in a way I’ve found reliable for both orchards and vegetables. But the real question isn’t just “does it work?” Instead, folks need to ask: “What happens if I combine it with other agrochemicals on my spray list?”

Mixing copper isooctanoate with fertilizers, insecticides, or other fungicides isn’t as clear-cut as the label might promise. Some growers report good results teaming this copper with organophosphate insecticides or standard foliar feeds. In warm-season vegetables, copper isooctanoate often goes out with basic nutrition blends or wettable sulfur, and both work fine as long as the pH stays around neutral. Once the pH drops below 6 or surges above 7, things get dicey. Precipitation and sludge start to appear, and spray jobs become headaches.

Tank-mixing copper products with phosphonates, mineral oils, or certain surfactants spells trouble in many cases. In my experience, adding phosphonates leads to thick flotations that clog filters and valves. Some surfactants will knock copper out of solution—bad news for spray rigs with fine mesh screens. If your operation depends on low-drift nozzles or mist blowers, any thickening or particulate will shut down the system fast. Lab research backs up these field observations: studies out of agricultural colleges in Italy and California track these same incompatibility issues, with a focus on precipitation, physical changes, and crop damage.

Growers looking for smooth tank mixes need to keep things simple. Every time a new product is added, perform a quick jar test: mix a pint of water, add the products in the exact order and rate, and check for cloudiness or separation in the first fifteen minutes. In most cases, copper isooctanoate won’t get along with products that are acidic or highly alkaline. Black spots or flakes appear quickly if the chemistry starts to break down.

Most extension agents will point you toward manufacturer-approved compatibility charts, updated every few years as new results come in. But nothing beats hands-on testing. Take time to call the technical helpline on the label, as companies often keep an internal list of both successes and near-misses sent in by other growers. If the answers seem vague, it’s for good reason: every well or irrigation source brings a different water profile, and hard water will force even a perfect mix to separate.

In every spray program, looking for compatibility between copper isooctanoate and other chemicals cuts down on wasted time, crop stress, and failed controls. Manufacturers would do growers a big favor by sharing more real-world mix data, and university extension agents could keep conducting side-by-side jar tests with popular combinations. Out in the field, taking five minutes for a jar test saves hours cleaning filters and protects plant health in a way no “compatibility statement” on a label ever can.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper 4-methyloctanoate |

| Other names |

Copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate Copper 2-ethylhexanoate Copper octoate Copper(II) octoate Copper(2+), bis(2-ethylhexanoate) Copper bis(2-ethylhexanoate) |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒpər aɪ.səʊˈɒk.tə.neɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 16674-15-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1206966 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:91759 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL4297651 |

| ChemSpider | 25968054 |

| DrugBank | DB14479 |

| ECHA InfoCard | EC#: 257-386-1 |

| EC Number | 205-250-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 11320 |

| KEGG | C15671 |

| MeSH | D003937 |

| PubChem CID | 16211214 |

| RTECS number | RT0350000 |

| UNII | NU19XM74SB |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8022742 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C16H30CuO4 |

| Molar mass | 470.10 g/mol |

| Appearance | Blue-green powder |

| Odor | Characteristic |

| Density | DENSITY: 1.0 - 1.2 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| log P | 0.14 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.23 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 4.7 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −6.5×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.437 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity: 12 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.84 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 596.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | QH52AG03 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H410: Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P333+P313, P362+P364, P391, P501 |

| Flash point | > 96 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ (oral, rat): > 2000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | > 940 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | GN1380000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2000 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Copper(II) octanoate Copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate Copper naphthenate Copper stearate Copper laurate Copper(II) acetate Copper(II) oleate |